Action needed to address indirect sourcing 'blindspot'

Traders, food manufacturers, retailers and governments must take action to reduce the deforestation risks associated with indirect – and often unknown – sources of commodities, according to new research.

Almost three-quarters of deforestation is driven by agricultural expansion, the main culprits being beef, cocoa, soy and palm oil. Deforestation threatens the livelihoods of millions of forest-dependent people, is a major cause of climate change and biodiversity loss, and even risks undermining the viability of future agriculture.

Multinational commodity traders such as Cargill, Bunge, Olam and Wilmar are central to efforts to eliminate deforestation from global supply chains. These large companies handle the procurement and export of most of the world’s commodities, connecting hundreds of thousands of farmers with millions of downstream customers. Pressure is growing on traders to reduce their impacts, most recently by proposed EU legislation prohibiting the import of commodities grown on recently deforested land. At the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, ten of the world’s largest traders pledged to eliminate deforestation.

It is often assumed that traders buy commodities directly from farmers and therefore know where their products are grown. This is not the case, according to new research by our team UCLouvain and Trase published in Science Advances. It shows that large volumes – if not the majority of some commodities – are bought indirectly through local brokers or other intermediaries who aggregate commodities grown on many farms before selling them to traders for export. This makes it difficult to identify the source of the commodity and whether it was grown on deforested land, creating a blindspot in many sustainable procurement activities.

Quantifying indirect sourcing

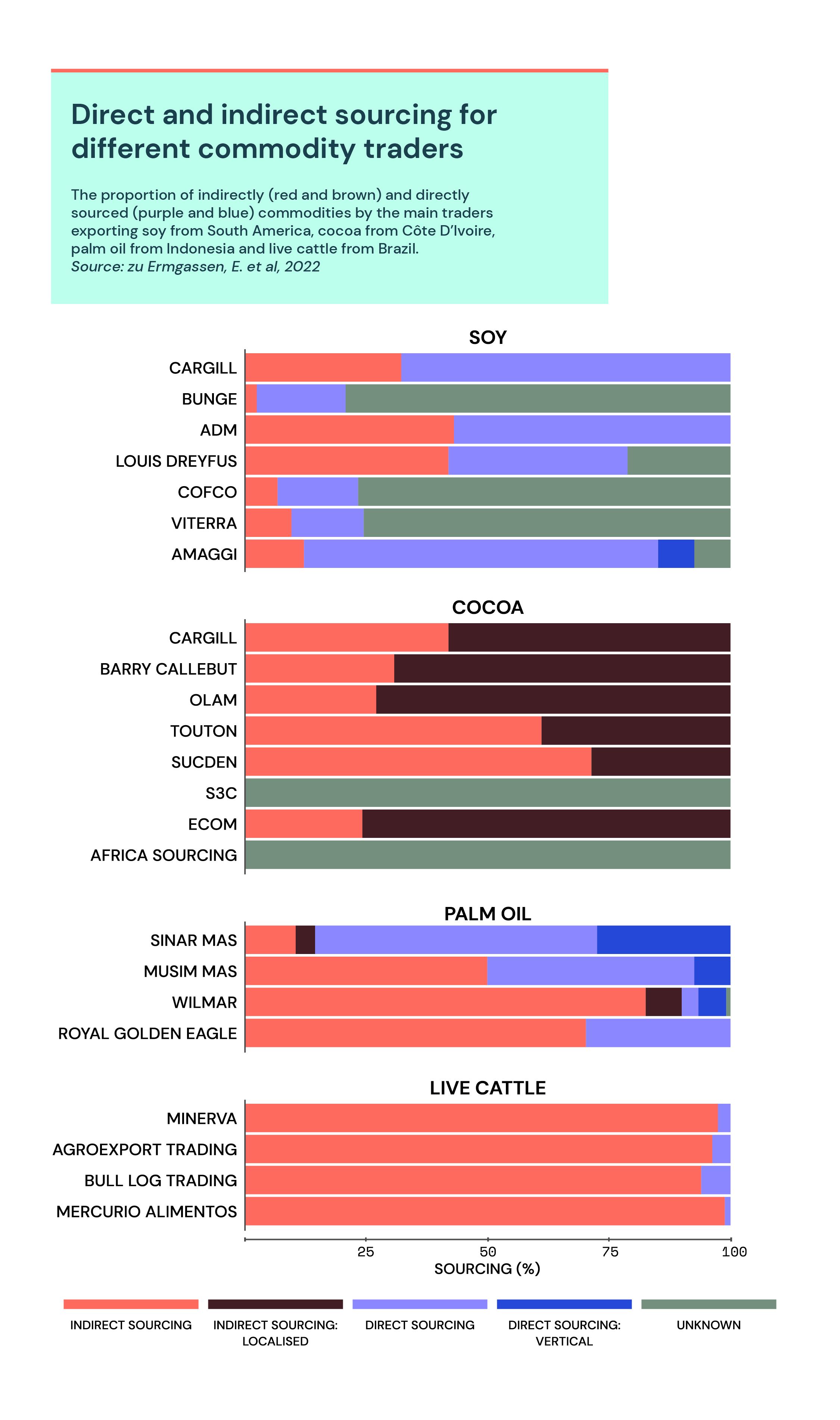

We assessed how common indirect sourcing is for four key commodities where deforestation is a big challenge: live cattle from Brazil, cocoa from Côte d’Ivoire, palm oil from Indonesia, and soy from South America. Combining data from customs records, corporate disclosures, animal movements and farm production, we calculated the level of indirect sourcing by the traders handling the top 60% of exports in each case. We then assessed how traders address sustainability risks in their supply chains.

Overall, indirect sourcing accounts for 12-44% for soy, 15-90% of palm oil, 94-99% of live cattle and 100% of cocoa. For palm oil, the wide variation between companies reflects differences in the sourcing of refined palm oil, which has greater reliance on indirect sourcing, compared to crude palm oil.

For example, Barry Callebaut, a leading cocoa trader and chocolate manufacturer, is estimated to source one-third of its cocoa from cooperatives, each of which has an average of more than 500 farmer members. Here, bean-to-bar traceability is clearly a challenge, though the trader may at least know the approximate origin from the cooperative’s location. The remaining two-thirds of the company’s cocoa is sourced through intermediaries known as ‘traitants’. This is even more opaque, as cocoa is often exchanged at the port and may be of completely unknown origin.

In the case of cattle, they may be born on one farm, reared on a second and fattened on a third before being bought by a trader. For example, suppliers to Minerva, the largest cattle exporter, each bought cattle from 20 other indirect suppliers on average.

The risks of deforestation and other impacts are often higher in parts of the supply chain where companies have least visibility. For four out of six cocoa traders assessed, deforestation risk was higher for cocoa supplied by traitants than through cooperatives. In the Brazilian cattle sector, indirect suppliers to slaughterhouses are 42% more likely to deforest than direct suppliers.

Though traders have begun to acknowledge the challenge that indirect sourcing poses for sustainability monitoring, progress is slow. Brazilian meatpackers operating in the Amazon are still setting up systems to monitor indirect suppliers for deforestation, though many began monitoring direct suppliers over a decade ago.

The two biggest traders in the soy sector, Cargill and Bunge, admit they are still ‘finding solutions to trace all these [indirect] supplies’. Bunge, for example, only monitors 30% of the soy it sources indirectly. The Cocoa and Forests Initiative, signed by leading cocoa companies together with the governments of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, sets targets for traceability of cocoa sourced via cooperatives, but not for cocoa sourced via other intermediaries which accounts for 20-70% of cocoa supplies for each trader.

Bringing indirect sourcing into the fold

Risks arising from indirect sourcing cannot be addressed by simply switching to 100% direct sourcing. Increases in direct sourcing would favour large producers over smaller (and often poorer) ones, and could disrupt local economies and increase commodity prices.

In many cases, a shift to direct sourcing is not realistic as the physical characteristics of the commodity lend themselves to aggregation early in the supply chain. Fresh palm oil fruit bunches, for example, are friable and need to be processed within 48 hours to avoid spoilage. They are therefore aggregated and processed locally into crude palm oil before long-distance transport. Similarly, the transfer of cattle between farms is a feature of livestock farming in all parts of the world.

Governments in producer countries can do more to help increase transparency of indirect supply chains. In Brazil, for example, animal transport permits are an important means to identify the origin of cattle, but the authorities do not make them readily accessible. Côte d’Ivoire’s coffee and cocoa board has information tracking production from farmers to the buyer and on to the point of export. Making this data public would facilitate trading companies to trace the cocoa in their supply chains. There is also a role for the EU and governments in consumer countries to support these efforts through strengthening the implementation of its proposed regulation.

Achieving systemic change

So-called ‘landscape’ or ‘jurisdictional’ approaches, which aim to improve sustainability across a region rather than a specific supply chain, are also an important piece of the puzzle. These initiatives bring together producers, traders, government and civil society to tackle the systemic drivers of deforestation.

While these efforts are championed in many corporate sustainability reports, they still lack serious investment. The Consumer Goods Forum’s Forest Positive Coalition of Action, which includes the likes of Carrefour, Mars, Mondelēz, Nestlé and Unilever, highlights landscape initiatives as one of four pillars in their sustainable sourcing efforts. Yet their collective annual investment is only US$9m – a fraction of a percent of their combined annual profit.

Commodity supply chains are complex. To deliver on promises to eliminate deforestation, traders and industry sustainability initiatives need to recognise, monitor and report on indirect sourcing to ensure it does not remain a barrier to delivering on sustainability goals.

Erasmus zu Ermgassen is a Trase researcher based at UCLouvain and is lead author of the paper “Addressing indirect sourcing in zero deforestation commodity supply chains” published in Science Advances, 29 April 2022.